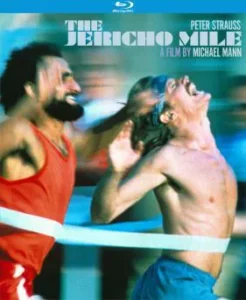

Michael Mann’s films have become almost legendary for their authenticity, attention to detail, and realism. This mystique began with his first film, The Jericho Mile, a TV movie released in 1979. Although perhaps Mann’s least remembered film, it illuminates how a movie production can shoot for authenticity and challenge what authenticity means, especially for the real people depicted on screen. These days, with politicians and tech oligarchs attacking reality itself, we continue to interrogate art’s relationship with truth, especially when it purports to depict real places, people, and events.

Michael Mann spent the 1970s moving out of commercials and documentaries and into network television. He wrote several episodes of Starsky & Hutch and Police Story and then got the chance to direct an episode of Police Woman. The next step in his career path was to direct a feature film.

During this time, he honed his writing abilities and industry connections, but he also began approaching his subjects with an eye towards verisimilitude. This started with his documentary work, such as Insurrection (1970), about a student revolt in Paris, and the American road trip short film 17 Days Down the Line (1972). But Mann really got going in 1978, when he did some uncredited writing on Ulu Grosbard and Dustin Hoffman’s 1978 crime drama Straight Time. Part of this work included visits to Folsom Prison in California, where he spent considerable time drinking in the atmosphere and interviewing inmates.

Observing the environment within Folsom ignited Michael Mann’s imagination. So he went looking for an existing script to serve as a jumping-off point for his project. To reduce costs and thus make a film more likely to be greenlit, Mann looked for something the executives at ABC already had the rights to. He recalled:

I’d been interested in making a movie set in a prison and managed to get inside Folsom… This just emphasised, crystallised what I wanted to do. So we looked around for something that we could use. They’d had this script, The Jericho Mile, lying around on a shelf at ABC for around ten years! – Fox (1980)

The script he found revolved around an inmate, Rain Murphy, a white man incarcerated for first-degree murder, who spends his time running track and staying aloof from the various gangs that organized the prison population. The action centers on Murphy’s attempt to gain entrance to the upcoming Olympics, on the one hand, and the tragic downfall of his friend Stiles, a black man, through the machinations of a white gang leader. Time is a central theme – whether you’re doing time or whether time’s doing you.

The Jericho Mile broadcast on ABC in early 1979 and released theatrically in Europe. Mann’s directorial debut received considerable critical praise. Indeed, when it came time to divvy out awards, the film received four Emmy nominations and three wins (Parish, 2000). Much of the praise centered on its remarkable sense of place, its authenticity, especially for a TV movie that had precious little prep time or budget.

Kevin Thomas of the LA Times, for instance, concluded his review by praising both The Jericho Mile‘s authenticity and its attempt, however imperfectly realized, to try something daring: “Filmed entirely at Folsom State Penitentiary in California…, ‘The Jericho Mile’ benefits strongly from its authentic settings. If it had tackled more than it could handle, it is nevertheless an instance of the big attempt to be preferred to the small success.” (Thomas, 1979)

Much of this vaunted verisimilitude was credited to two things: that Michael Mann opted to film inside the walls of Folsom, and that he included actual prisoners among the cast and crew. This allowed him access to a level of reality that most TV productions could not match. For instance, according to Mann, the weapon props used in The Jericho Mile were based on real pieces recovered from the prison: “All the weapons we used in the film were rubber models made from real weapons that had been used in stabbings and killings and were then thrown away. They’d been borrowed from the prison.” (Fox, 1980)

Michael Mann wasn’t the only one interested in accuracy in The Jericho Mile. According to lead actor Peter Strauss, the prisoners, too, “were very anxious to see that we did things accurately.” Proper language was a particular point of focus for the imprisoned advisors. Strauss gave one example where a prisoner overheard one actor shout to another, “Honkey!” This convict responded, “Honky? I haven’t heard that in 10 years!” The actor asked what to use instead, and the prisoner recommended, “How about ‘white boy’?” This prompted another prisoner to chime in: “White boy?! You a ——! Everybody knows you’re supposed to say ‘hoogie’!” So the actor went with hoogie. (Beck, 1979)

The prisoners also concerned themselves with the look of The Jericho Mile, particularly how the cells were decorated. Peter Strauss recalled: “We had fixed up one cell to shoot in and some of them told us, ‘Hey, this isn’t it. Why tell the public this is a country club?’” Mann and his team took advantage of this interest among the inmates. As Strauss put it: “In the end, our cells were decorated by the inmates themselves, filled with their own things. They also didn’t want our cells to look too bare because they didn’t want to be depicted as animals in a cage.” (Beck, 1979)

A Big Picture View of The Jericho Mile

As a historian, I try to judge fictional dramas charitably. Minor inaccuracies that might have resulted from, say, budgetary constraints are easy to forgive. Compressed characters and paraphrased dialogue are often necessary to fit the drama into a serviceable runtime. Instead of these nitpicks, I look for big picture errors: has a crime been whitewashed (e.g., D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation), a marginalized group erased from the historical narrative (Roland Emmerich’s Stonewall), or government propaganda smuggled into a supposedly authentic portrayal (Kathryn Bigelow’s Zero Dark Thirty)?

These are some of the questions I ask myself when judging a piece of art’s historical accuracy and political ideology. If possible, I also consider the opinions of the actual participants in the dramatized events. This is critical to consider when the subject matter is something about which most of us have no direct knowledge and depicts participants with very little structural power. In the case of The Jericho Mile, therefore, we might ask what the prisoners themselves had to say.

As it turns out, inmate Bob Collins, writing for the prison newspaper Folsom Observer, gives us an answer. In his review of the film, he presented a multifaceted analysis that tried to point out its most unrealistic elements while considering the need to tell a good story. Collins began his article by breaking down the various ways one might judge the picture and came away largely impressed with the finished product, with one notable exception:

There were three ways to look at this movie: artistically, realistically and philosophically. Artistically, the photography was excellent and the acting was super; philosophically, the story line was good, proper emotion was elicited, i.e. Strauss as Larry Rain was not going to cop-out to the system. He knew that he was wrong and was willing to pay for it and would not concede to the bureaucrats even at the expense of blowing his chance to run in the Olympics. Realistically, it was a bomb!

If people believe prison life, especially in Folsom, is anything near the way it was depicted, there is no telling what public opinion was of prisoners the day after airing. (Collins, 1979)

Collins tried to weigh the needs of drama against the pressures of realism, yet still found the overall product pretty far from the mark:

A degree of fantasy is necessary in any production, but in Jericho Mile, there were too many overly phony scenes (the sword fight in the yard, the fight scene in the laundry, the apparent laxness of security…a convict serving a life term being permitted to run outside the security perimeter, among many other unbelievable scenes…[And given how easy the producers seemed to think it was to smuggle drugs into the prison,] it would appear that Hollywood knows more about prisons than those who work and live in them. (Collins, 1979)

Ever circumspect in his criticism, however, Bob Collins recognizes that, had the prisoners been given final script approval, “the movie would not have been produced and we wouldn’t have made money [i.e., been paid for their work on the film].” Nevertheless, Collins offers a blueprint for a better film: “[It] could have been a great movie if more emphasis had been put on the man and less on what Hollywood considered ‘prison politics.’ More emphasis could have been put on ‘real life’ and a closer balance between the two (fantasy and realism) would have produced a believable movie.” (Collins, 1979)

While The Jericho Mile might not have bestowed upon the viewing public a newfound understanding of prison life, Collins did see some positive results from the film having been made: “…we got a sorely needed track, a new ice machine, made a few dollars and hopefully enlightened Peter Strauss about life in prison.” (Bob Collins, 1979)

He ends the article by quoting the opinions of 15 inmates. The majority consider The Jericho Mile either good or average quality. The most common complaints echoed those of Collins, that the film was unrealistic and inauthentic.

Michael Mann never said he set out to make a documentary, and thus freely admitted that he took artistic liberties. In a 1980 interview he focused on inaccuracies of prison language in The Jericho Mile, framing his changes as an attempt to add a little more poetry to the script: “…it’s all real language and yet I manipulated it around, so you do have that kind of poetical quality about it.” (Fox, 1980)

A decade later, when asked about historical accuracy in 1992’s period drama, The Last of the Mohicans, Mann said flat out:

My mission is not to be historically accurate and immensely boring. I’m using history, not doing it. I telescope events, combine characters, put quotes from one man into the mouth of another. I’m working like a collagist, combining elements to re-create the spirit of the time. (Dutka, 1992)

In other words, Michael Mann wants accurate details and accurate vibes, but he’s willing to sacrifice chronology and specific personality to attain this within a dramatically interesting structure.

So what of The Jericho Mile? Mann’s attention and commitment to detail give the prison drama depth and a lived-in quality. No Hollywood set could mimic the actual environment of an active prison, especially not on a TV budget. The addition of real prisoners injects the proceedings with a sense of believability, even if some of what they’re made to do would never happen in real life.

While inmate Bob Collins considered the film’s realism to have bombed, I can’t help but focus on his summation of The Jericho Mile‘s philosophical message: “Strauss as Larry Rain was not going to cop-out to the system.” Indeed, the Olympic bureaucracy is even compared to the gang-organized prisoners around him. As powerless as Murphy was under the prison leadership, he remained powerful in himself, defiant and liberated. At least in his mind. This seems like the kind of victory a tiny cog in a massive machine might be able to attain: not letting the punishment bureaucrats break him.

In making The Jericho Mile, Michael Mann attempted to craft a film for prisoners rather than one simply about them. The plot ultimately recognizes the limits of what Murphy can do, but within those walls, it crafted for him a substantial victory. There is, then, a deep vein of humanism running through the film, which gives Murphy a depth of feeling and a degree of power that doesn’t, via plot contrivance, tip into the saccharine. If The Jericho Mile has a touch of Rocky-esque sentimentality, it maintains the first Rocky’s commitment to little victories (Rocky goes the distance but does not win the fight). It avoids the sickly-sweet nonsense of the sequels.

The Jericho Mile still works within the limits of the Hollywood system and the confines of 1970s television. The actual politics of incarceration in the US are ignored, and the other prisoners are far less fleshed out than the protagonist. These limitations, both of ideology and format, are important. As creators and critics, we should all work to understand – and smash – the structural constraints imposed upon our artistic expression.

All the more impressive that within those confines, Michael Mann chose as his first feature film a story where the prisoner, a murderer, won. Critically, this small yet meaningful victory has a ring of truth to it. In this sense, at least, The Jericho Mile has earned that much-vaunted adjective: realistic.

Works Cited

Anderson, Nancy. “A non-prison drama set in Folsom”. The Tribune (Oakland, CA), 23 March 1979.

Beck, Andee. “A chilling look behind bars”. The San Francisco Examiner. 13 March 1979.

Blau, Robert. “Mann-made hits”. Chicago-Tribune. 15 May 1986

Collins, Bob. “How inmates viewed ‘Jericho Mile’”. The Folsom Telegraph (reprinted from Folsom Observer). 11 April 1979.

Dutka, Elaine. “One Mann, Two Worlds”. LA Times. 20 September 1992.

Fox, Julian. “Four Minute Mile” in Steven Sanders and R Barton Palmer (eds), Michael Mann Cinema and Television, Interviews 1980-2012. Edinburgh University Press. July 2014.

Kennedy, Harlan. “Castle Keep”. Film Comment. December 1983.

Parish, James Robert. Prison Pictures from Hollywood: Plots, Critiques, Casts and Credits for 293 Theatrical and Made for Television Releases. McFarland. October 2000.

Thomas, Kevin. “Sure footing for ‘Jericho Mile’”. Reprinted in Herald News of Passaic, NJ. 18 March 1979.