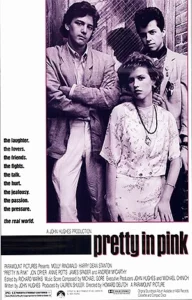

In The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, a political tract from 1852, Karl Marx proposed that “the tradition of all dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brains of the living.” Lately, the same could seemingly be said about the films of John Hughes, perhaps especially Pretty in Pink.

Contents

Forty or so years after the director’s 1980s heyday—the time of The Breakfast Club (1985), Ferris Bueller’s Day Off (1986), and Pretty in Pink (1986)—Hughes’ films trouble our collective pop culture consciousness more than ever. This past week, the cast of The Breakfast Club reunited for the first time in decades. Earlier this month, another of Hughes’ iconic films, Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, was widely referenced in the media for its comic treatment of Depression-era tariffs, as explained by the titular protagonist’s high school teacher, played by the perennially wry Ben Stein.

Byliners suggested that we glean wisdom from John Hughes’ discussion of tariffs, especially as we debate Donald Trump’s current tariff plan. Even current Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell had Hughes’ film in mind. Marx continues in Eighteenth Brumaire, explaining that in “epochs of revolutionary crisis [people] anxiously conjure up the spirits of the past to their service, borrowing from them names, battle slogans, and costumes.” Somehow, we live in a time when even America’s top economists have marshalled Hughes’ films of teenage limerence in hopes of swaying public opinion.

This all comes close on the heels of actress Molly Ringwald’s appearance on Monica Lewinsky’s podcast. Most famous for her work as the teen muse of Hughes, Ringwald admitted to Lewinsky that she had been “reassessing” her past relationship with the director. The podcast seemed a forum ripe for confession, yet Ringwald’s characterization of cineaste’s cradle-rocking interest in her as “peculiar” was ultimately more ambiguous than it was accusatory.

The legacy of the director, who would have celebrated his 75th birthday in February 2025, is equally ambiguous, particularly in terms of his politics. Internet interpretations of his work reveal disparate opinions regarding the ideological messaging in his films.

Does Pretty in Pink Suggest Capitalism’s Best Course?

At first blush, John Hughes’ coming-of-age rom-coms are far removed from the political sphere. Duckie’s record store Otis Redding, Allison’s Cap’n Crunch sandwich, and Ferris Bueller’s answering machine prowess may be creative, mischievous, even rebellious—but are they political? Surprisingly, many would say yes. Where to position Hughes’ films on the political spectrum remains a subject of debate.

In a 2006 article for Slate, Gen-X journalist Michael Weiss writes that although Hughes’ oeuvre feels lefty, the director himself “was actually a political conservative”, given that Hughes’ portrayals of down-and-out youth had more to do with celebrating the moral victory of the underdog than with championing the underprivileged. In Hughes’ hormonal vale of tears, snobs and elitists were the ones who ruined wealth for everybody else.” A more ad hominem and facile appraisal from 2010 brands the director as a “conservative republican”.

It would take seven years and the return of a Republican to the White House before corrective interpretations of Hughes’ films popped up in the mediasphere. Thus, a brilliant 2017 article by journalist Jeremy Allen characterizes Hughes as a type of “Brat Pack Marx” whose “message is loud and clear: No War but Class War”. These claims are extended, although with mixed success, in a 2019 article focusing on Hughes’ pièce de résistance, Pretty in Pink.

Ultimately, each of these readings of John Hughes’ films has a certain purchase, even as they all suffer from a common flaw: inattention to detail. This is especially true regarding Pretty in Pink, a film replete with references to the legacy of government economic intervention and, more specifically, the New Deal. The fact that the scripts for many of Hughes’ films are found online underscores the need for a closer reading.

Careful consideration of some of Pretty in Pink‘s key moments bears out the notion that the film is neither conservative nor leftist. Rather, it is an exploration of the death of the left. Written and produced following Ronald Reagan’s 48-state romp of Walter Mondale, John Hughes’ rollicking comedy queries what is left, if anything, of a Democratic-leaning, Keynesian-oriented working class.

As Reaganomics dismantled the legacy of the New Deal, Hughes’ films—subtly, tangentially, but unequivocally—interrogated both the character of US class relations and the cogency of Reagan’s policies. Pretty and Pink considers the question, already asked by academics, whether FDR’s policies—the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act, the Works Progress Administration, and the Emergency Banking Act—were meant to undo the Gordian knot of capitalism or save a system inherently driven to crisis from its herky-jerky machinations? Amid Reagan’s politics of retrenchment, rollbacks, and tax cuts, Hughes’ Pretty in Pink asks us: What type of society was the next generation going to be left with?

In 1984, Reagan, even while facing a US unemployment rate that hovered above a formidable seven percent, won by a landslide. Perhaps, as certain scenes in Pretty in Pink seems to suggest, capital might best realize itself and fulfil its promises via interventionism or neoliberalism. Perhaps FDR, the left’s cynosure during the second half of the 20th century, too, was an enthused capitalist. After all, isn’t that what Mr. Lorensax’s lecture in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off queries? In Pretty in Pink, the soundness of the New Deal vis-à-vis capitalism is examined from the film’s first minutes.

Pretty in Pink Illustrates the Left’s Malaise

With the opening sequence, the protagonist, Andie Walsh (Molly Ringwald), hurries through the halls of an affluent high school. On her way to class, she exchanges glances with the wealthy scion of McDonnough Electric, Blane McDonough (Andrew McCarthy). She also has an extended but exasperating conversation with Phillip “Duckie” Dale (Jon Cryer). Hughes’ script calls for “More money walking down the hall. Kids in expensive clothes.”

When Andie finally escapes Duckie’s ingratiating yet innocent come-ons, she arrives at a large lecture hall. Students listen as their teacher explains, “Some argue that the New Deal saved the capitalist system. And as evidence, the Roosevelt Administration was trying to avoid excess government power, rather than implant socialism. In his first act as president, Mr. Roosevelt enacted the Emergency Banking Act, and he refused to consider nationalization.” Perhaps, as Hughes’ educators suggest, FDR wasn’t the progressive iconoclast of the marketplace that we remember.

Of course, much of John Hughes’ masterpiece points up the importance of characters’ respective economic backgrounds. The creative protagonist, Andie, comes from the working class and struggles with her feelings for Blane, a wealthy and popular student. Blane’s elite lifestyle conflicts with the DIY values of Andie and her best friend, Duckie. The power of money, class conflict, and the malaise of the left are constant topics of conversation.

Iona (Annie Potts), Andie’s manager at the record store where the protagonist works, is described in Hughes’ script as “a thirty-five-year-old ex-peace bum.” In the shop, Andie and Duckie overhear a telephone conversation between Iona and, ostensibly, another forgettable loser boyfriend she needs to tell off. “Every time you go to the John, you lose IQ points!” she lambasts him. Upon realizing that both Andie and Duckie are eavesdropping on the call, she covers up the mouthpiece of the phone and jokingly whispers the (supposed) identity of her interlocutor, all while rolling her eyes: “Walter Mondale,” she winks.

Clearly, the Minnesota politician couldn’t even inspire former hippies. Now a small-business owner, perhaps Iona finds herself more motivated by Reagan’s promised tax cuts.

Pretty in Pink‘s Message About Working-Class Resignation

The legacy of the left, once a powerhouse for the US working class, languishes in Pretty in Pink. Also striking is a scene in the high school library, a few scenes after Andie and Blaine have made a few indications of their mutual interest. Concentrating studiously, Andie sits at a computer. According to Hughes’ script, she is “doing a paper on the WPA.” Both viewer and Andi read “More than 8,500,000 men and women were employed in building and improvement jobs, and” before the text cuts out. “Do you want to talk?” flashes across the screen.

Via some intranet connection, the wealthy and handsome Blane has found Andie. Standing up from her computer, she realizes her crush is sitting directly across from her. Goofy smiles ensue. Blane’s phantasmagorical wager from above, this deus ex machina, doesn’t go in vain. Indeed, it almost seems like Andie, not unlike many of the wage earners during the 1980s, can’t help but believe that the best offers always trickle down from above.

For almost all of the working-class heroes in Pretty in Pink, resignation of the left’s demise and capitulation to society’s rich appear to be the only reasonable solutions to their problems. Thus, when Andie explains to her friends Jena and Simon (Alexa Kenin and Dweezil Zappa) that she’s falling for Blane, Jena urges Andie to overlook class differences; of course, Blaine’s top-down proposal is viable. Jena tells Andie that class differences don’t matter: “I mean, it’s material.” Simon agrees, explaining that should his father magically come home one day a rich man, he (Simon) would willingly “Kiss his ass.”

In a similarly defeatist vein, Andie explains to Duckie that “whether or not you face the future, it happens.” Andie’s father, in turn, has to accept not only that he needs to look for a job, but also that his wife, who left him, is not coming back. When Andie gets into trouble with some of the rich girls, she finds herself in the office of the Dean of Students. There, the Dean, Mr. Donnelly (Jim Haynie) explains to the protagonist that “if you put out signals that you don’t belong, people are gonna make sure that you don’t.”

That is, even those born on the wrong side of the tracks need to act the part; after all, as Margaret Thatcher proposed while shilling for neoliberalism, there is “No alternative.” Blane is equally convincing at the end of Pretty in Pink when he tells Andie, “I believed in you. I always believed in you. You just didn’t believe in me.” Blane, a Great Communicator himself, succeeds in persuading Andie that the rich have always looked out for the little guy.

In his Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy, Marx explains that humanity “sets itself only such tasks as it can solve; since, looking at the matter more closely, it will always be found that the task itself arises only when the material conditions of its solution already exist or are at least in the process of formation.” Perhaps only now, at the dawn of what some are calling a post-neoliberal era and with another president swaying the hearts and minds of the working class disingenuously, are circumstances ripe to fully understand the political meaning of John Hughes’ brilliant films. They let us meditate on the slow death of the left.

Works Cited

Allen, Jeremy. “The ‘Pretty In Pink’ Soundtrack Was a Gateway to Alt-Pop and Proletarian Revolution”.Vice. 9 June 2017.

Associated Press. “Fed Chair Powell Recalls Ferris Bueller in Chicago Speech.” NBC Chicago. 16 April 2025.

Brenner, Johanna Brenner, Robert. “Reagan, the Right, and the Working Class”. Verso Books. 15 November 2016.

Deennice, 80s. “Post on 80s Culture and John Hughes”. Threads. 18 April 2025.

de Visé, Daniel. “Why Trump’s tariffs have everyone talking about this scene from ‘Ferris Bueller’s Day Off‘”. USA Today. 4 April 2025.

Edell, Victoria. “Molly Ringwald Says She Now Feels ‘Something Peculiar’ About Being Called John Hughes’ ‘Muse’ for ’80s Teenage Movies”. People. 12 March 2025.

Fraser, Steve and Gerstle, Gary. The Rise and Fall of the New Deal Order, 1930–1980. Princeton University Press. February 1990.

Glick, Jared. “The Political Conservatism of John Hughes”. Slate. 21 September 2006.

Jamieson, David. “Trump, Protectionism, and the Future of Neoliberalism”. Jacobin. 20 April 2025.

Johnson, Alex. “Ferris Bueller ‘Holds Up’ a Mirror to the Economy”. YouTube. 4 April 2025.

Marx, Karl. The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte. Marxists.org. 1852.

—-. “A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy.” Marxists.org. 1859.

Olsen, Henry. The Working Class Republican: Ronald Reagan and the Return of Blue-Collar Conservatism. HarperCollins. June 2017.

Pinaire, Kaitlin. “Pretty in Pink: A Critical Political Marxist Perspective”. Medium. 13 January 2019.

Smith, Kyle. “John Hughes: conservative Republican”. New York Post. 30 September 2010.

Walker, Grant. “The Screenplays of John Hughes: Read Them Here.” Cinema Bandit. 20 July 2018.