Some might think we have had enough documentaries about New York City in the mid-to-late 1970s. These people can be described as misinformed, misled, or simply missing the point. There is a good reason filmmakers continue to produce documentaries about this period, and will likely do so as long as the form exists, as they do again with Drop Dead City.

New York City during this period was a thrilling yet terrifying cacophony of crises and epiphanies that turned the place into an accidental experiment on whether cities, as we know them, would survive. Not making documentaries about that era in this city makes as much sense as asking historians to stop writing books about the Roman Empire.

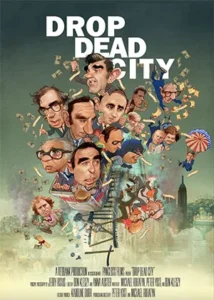

That said, Michael Rohatyn and Peter Yost’s entertaining and unexpectedly poignant documentary Drop Dead City seems to test this thesis. A feature-length film on this narrow and complex a subject—the fiscal crisis that nearly gutted the city in 1975—has potential to be challenging, no matter how colorfully gritty the period footage is.

Yet Drop Dead City succeeds superbly by embracing the abstruse density of its economic subject (viewers will learn a lot about the municipal bond market), yoking those numbers to real-world impacts, and using that connection to present a sincere paean to the ideal of what a modern progressive city can be. It also helps that, despite the interviewees’ wonkishness, being New Yorkers, they deliver their stories with slyly cutting wit, theatrical gusto, or just straight profanity. The filmmakers have a lot of material to work with.

Drop Dead City begins with the unlikeliest of characters being sworn in as mayor in January 1974. Abe Beame was a short guy from Queens who came to power through the twisty byways of mid-century borough Democratic machine politics. Nobody expected much from Beame, an unflashy caretaker type known for being “good with money” who barely registered in the shadow of his predecessor, the very flashy and Kennedy-like John Lindsay, and yet was thrust into the spotlight.

The first of many bits of black comedy served up by the filmmakers comes not long after Beame takes office. Stephen Berger, who ran one of the emergency groups put together to navigate New York City out of the financial crisis, describes what was discovered when comptroller Harrison Goldin finally dug into the city’s books: “There were No. Fucking. Books.”

After Goldin blared his discovery to the press, the stunning news that New York City’s finances were an unholy mess, compounded of wishful thinking and at times nonexistent management, set off municipal chaos. One of Drop Dead City’s more vivid stories is of the auditors discovering mounds of canceled checks in a forgotten pile. The filmmakers present this as an urban policy nightmare, in which each pillar supporting the city government’s fiscal assumptions was knocked down one after the other.

New York City’s revenue base had been dwindling since the late 1950s, when middle-class people began moving away. City leaders plugged revenue gaps by issuing bonds, which banks had readily purchased. However, when the dire extent of the municipal debt became clear, interest rates on that debt rose, and the banks suddenly lost confidence. By 1975, the city faced a previously unthinkable choice: Layoffs.

The filmmakers portray this crisis with a zesty appreciation for the drama. At each step, dry facts and figures are translated into palpably physical terms. (Though there is a comedic abstraction to some of the economic chicanery discussed, like the discussion of “tax anticipation notes”, literally bonds issued on the assumption that tax revenue would be coming, though that didn’t always happen.) Yet the money is never just money. Smaller budgets meant fewer workers, resulting in fewer services for a city already struggling to retain its residents.

Drop Dead City churns through the crisis of 1975 on two tracks. The first is a city imploding. At a time when precincts like Brooklyn’s “the Seven Five” were seeing a murder a day, City Hall lays off 5,000 police. As arson scorched the city skyline, firefighters were dismissed. Sanitation workers are let go, as are teachers by the thousands. All the underpinnings of a modern city are cut to the bone. Massive protests heave with suddenly unemployed and furious workers who look on the verge of pulling a Bastille.

At the same time, the filmmakers use multiple first-person accounts from advisers who participated in the frantic financial negotiations to relate the dramatic ups and downs of Beame’s fight to stave off municipal bankruptcy. The bankers and academics on the blandly named Municipal Assistance Corporation attempted to locate lost change in the couch cushions and negotiate between City Hall, the unions, the state government, banks, and eventually the federal government.

As New York teetered on the edge of default and unions deployed in battalion strength around the city, President Gerald Ford was given the opportunity to throw the city a lifeline. Although Ford was a moderate Republican, Drop Dead City argues that, trying to stave off a primary challenge from a popular far-right crusader named Ronald Reagan, he initially refused to help, leading to the infamous New York Daily News headline: “Ford to City: Drop Dead”.

While these stories plow forward on the street and in conference rooms, Drop Dead City also pulls a neat trick by stepping back and considering what it was all for. At multiple points, spaced between some lengthier segments of footage showing daily life in the city, which are edited with an almost symphonic sensibility, the filmmakers include reminders from their interviewees about the promise and idea of New York City.

People rhapsodize about New York as the great American escalator, reliably providing immigrants and the working poor with a chance at a better life. The plentiful jobs in manufacturing or city services, vibrant culture, and amenities like public hospitals and the free City University system created the promise of a seemingly permanent and stable middle-class city.

Though economic changes and an ever-growing city workforce made that promise impossible to sustain by 1975, the film does not deride the idea of a city not just for the poor and the wealthy as foolish or utopian. As dramatic as its story of New York City’s fight against financial death is, what makes Drop Dead City so compelling is what it says about the gutsy urban idealism that fueled the fight.